Betty Hutton's Miraculous Recovery

A very American story about a star who captured America's heart

Child, never forget this moment—this happiness—not even if they’ve broken your heart and you’re trying to put the pieces back together again… you’ve a brave heart, child. And brave hearts, like all rare and fine things, are easily broken.

—Miss Gibbs (Constance Collier) to Pearl White (Betty Hutton), The Perils of Pauline, Paramount Pictures, 1947

Betty Hutton, glittering Hollywood star of yesteryear, infused America with her trademark optimism during World War II. But her own life, which ended 16 years ago today, was often the polar opposite of what she projected on the screen. Hers would have been a tragic ending—like so many in Hollywood—but for a miraculous intervention.

All Heart

TCM Host Robert Osbourne opened up his “Private Screenings” interview with Betty Hutton in April 2000, noting she was someone who wore her heart on her sleeve, to which she replied: “I like to make people happy. It does something to my soul.”

She was all heart—and, as a consequence, totally vulnerable. It was the secret of her success—and her suffering. This vulnerability—and strength—was revealed in a conversation, recounted for Osbourne, that she had with Al Jolson, as he was finishing out his Broadway career and she was just starting out: “‘Mr. Jolson, I am so scared.’ And, he said, ‘Good, kid. I throw up before each show.’ He said, ‘Betty, if you lose that, you’re through.’”

A Star Is Born

Betty got her first break closer to home in Detroit with Vince Lopez’s Orchestra as lead vocalist. But, before long she was performing in New York at Billy Rosa’s Casa Manana, dazzling audiences—including Buddy DeSylva, who tapped her for Cole Porter’s Panama Hattie on Broadway starring Ethel Merman—the show she was doing when she met Jolson. When Merman cut Hutton’s number, DeSylva confided to Betty he was slated to head Paramount production and promised to make her a star—if she would stick with the show. She had film experience having made a couple of Warner Bros. shorts with Lopez in 1939 in which she was dubbed “America’s No. 1 Jitterbug” for her mugging and wild gestures.

In 1940, Hutton arrived in Hollywood, then a relatively small orange-tree-scented town, and signed a contract with Paramount the following year. Her trademark exuberant performance in 1942’s The Fleet’s In wrapped in bundles of talent and energy—“a vitamin pill with legs,” Bob Hope quipped in “Command Performance”—made her Paramount’s top female star almost overnight.

As her good friend, the late A.C. Lyles, an 85-year Paramount veteran, told me, her “Arthur Murray Taught Me Dancing in a Hurry” number “just exploded on the screen and… from there she just became one of the most important stars we’ve ever had at Paramount and made picture after picture after picture”—a dozen by 1950 including The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek (1943) and The Perils of Pauline (1947).

Along the way she became a hit recording artist with such chart toppers as Hoagy Carmichael’s “Doctor, Lawyer, Indian Chief”—one of the “great songwriters” who worked with her. And, she was a popular live performer, as well.

“I just performed with all my heart,” is how she described her approach for Osbourne.

She epitomized the fresh, innocent American spirit: can do—“Oh, I couldn’t sing good, but, boy, I sure sang loud,” was one of her famous lines—and completely unselfconscious—“Gosh, Mom, isn’t that a lucky break” was her constant refrain.

It was, in fact, her mother Mabel’s unlucky breaks that sparked her entry into show business.

Hardscrabble Early Life

Born Betty June Thornburg in Battle Creek, Michigan on Feb. 26, 1921, Hutton never knew her father; he had skipped town when Betty was two.

Her earliest memory—“like it was yesterday”—dated back to when, at age three, she spontaneously broke into song to distract a drunken man threatening to beat up her mother at the “Blind Pig” she ran during Prohibition. Soon, little Betty, joined by sister Marion, began belting out such favorites as “Black Bottom” at her mother’s Speakeasy—in constantly changing venues two steps ahead of the police.

In 1929, the family moved to Detroit looking for greener pastures. But, life was hard and Mabel was hard drinking—forcing Betty to sing on street corners for “nickels and dimes.”

Her mother discovered Betty had real talent at age 9 when she sang in a school production—her first public performance. As a result, according to reports, she started taking Betty around Detroit to perform for any group that would listen. Or, as Hutton told it, “I quit school when I was nine years old and started singing on street corners because my mother was an alcoholic.” Later, when her mother took her to see a Charlie Chaplin silent film, she thought, “I’m gonna be a star and my mother will stop drinking.”

Hutton reminisced for Osbourne that when they returned to Michigan for the Let’s Dance opening, her mother, seeing the extremely heavy police presence protecting Hutton, now “a big star,” humorously assessed their changed fortunes by quipping, “at least this time they’re in front of us.”

In 1950, Betty Hutton got the starring role and role of a lifetime in Annie Get Your Gun when Judy Garland was too exhausted to continue filming.

From Pinnacle of Success to Rock Bottom

Her 1950 success in this film version of Irving Berlin’s hit musical about Annie Oakley should have paved the way for much greater success. But, as Hutton summed it up, Annie Get Your Gun “killed the performer in me.” The whole experience, she said, “was the heartbreak of my life.” While none of her pain was evident on screen—she projects a confident actress at the peak of her career—the cast and crew, she revealed for the first time in the Osbourne interview, were “terrible” to her. MGM did not even invite her to Opening Night in New York.

Not coincidentally, De Sylva, who had firmly managed her career—the only one to do so—died of a stroke that same year and, in 1952, Hutton walked out of her Paramount contract. “Paramount was Betty’s security blanket,” said Lyles. “And, when she left Paramount, she left a lot of her strength and a lot of her support.” “She never really recovered from that in many ways,” he added. “Her career didn’t recover from it and she had all kinds of difficulties, which is sad—sad.”

In Paramount’s place were many gigs and hoped-for comebacks along with the painkillers she began taking after injuring her arm while filming Cecil B. DeMille’s Oscar-winning Greatest Show on Earth.

By 1971, two years after Garland, who had become a friend on the Vegas circuit, died of a drug overdose at age 47, Betty Hutton—age 50, surveying four shattered marriages and a wrecked career—was on track for the same fate.

“I almost didn’t care anymore. I didn’t want to go on,” she told Osbourne.

Her mother had died on New Year’s Eve, 1961, in a fire. Five-and-a-half years later, Hutton declared bankruptcy. Soon Hutton found herself on the street in between living in seedy hotels, until one hotel, after kicking her out, took her to this minister who agreed to care for her until she got stronger.

“All she had was a shopping bag with a few things in it,” said Carl Bruno, executor of her estate. “I’ll never forget it. She was in one of those leather coats that the women wore in the 70s with the fur collar. And, it was all crinkled and peeling. I mean it was really very sad. And, I had no idea who she was.” Worth $10 million in the 50s and early 60s, she had lost all her money.

Over five years, she regained much of her strength—and singing voice—and then got a gig performing Anything Goes at a dinner theater outside of Boston. But, one night, while performing, she collapsed on stage—her 20-year addiction to prescription drugs and hellish private life, conspiring against her with frightening finality in a seeming replay of Garland’s fatal downward spiral three years earlier.

Miraculous Intervention

“I was on so many uppers and downers there weren’t enough pills to put me up or bring me down,” Hutton said. “I wanted to die.” When she entered a Boston rehab hospital, the 5’4” star recalled for the Herald News, “I weighed only 85 pounds and looked more dead than alive.”

Then, something miraculous happened.

Ironically, it was some 25 years after she had played silent screen heroine Pearl White in The Perils of Pauline, whose death-defying feats were directed by George McGuire.

On the verge of giving up, she looked out the window and was struck when she saw this priest calmly showing his ailing employee such affection and respect. And, she thought, “I’m going to meet that man. He’s going to save my life.”

The priest’s name was Fr. Peter McGuire. He was the pastor at St. Anthony’s Church in Portsmouth, Rhode Island. He had come to Boston to the rehab facility where Betty was recovering, to check in his cook, Pearl.

“He was a wonderful man,” said Professor James Hersh, Salve Regina University’s Philosophy Chair, who knew Hutton well. “I can see why she was so drawn to him…”

Fr. Maguire initially had no idea he had made any particular impression on Hutton. He didn’t even know who she was. But the minute Pearl was well enough to converse, she asked about him and learned he was a saint who helped everyone.

Hutton knew salvation when she saw it and soon decamped to Newport—as far from the Hollywood limelight as anyplace. As she said on Good Morning America in August 1978:

… if I hadn’t gotten (to Newport), I wouldn’t have made it. They didn’t expect me to be super great here. These people… took me in their homes, their little homes, and held me in their arms and kissed me and hugged me back to life. And, that’s New England, boy.

“Thank God,” said Lyles, “for Fr. Maguire because he probably saved her life… And, that was a period of hardship and work for her but it was a period that really, I think, saved her.”

Hutton, whose father abandoned the family when she was two, told Osbourne, “I never found me until Fr. Maguire… I (was) the product,” she said, “like hamburgers, hotdogs… Father said, ‘Betty, you’re just a hurt child. Let’s start from the word go.’”

She lived at the rectory during her five-year long recovery—cooking, washing dishes, making beds, cleaning, and enduring this lowly role by pretending she was playing The Song of Bernadette. In the process, she discovered “Christ is my heart” and converted to Catholicism.

In the early 80s, Hutton settled into a beautiful estate overlooking Newport Harbor and, for once in her life, enjoyed just being “Betty.”

“Her private life,” Hersh explained, “had been the source of so much pain that she was sort of setting it right. And, Newport was the place to undergo that transformation (and)… recapture who she was not on stage.”

The process was painful.

As Hersh tells it, one day in his Philosophy of Imagination course, they were discussing what Swiss psychologist Carl Jung calls “the shadow” where “right under the surface of the unconscious is an archetypal figure that everybody has that represents what he called our ‘inferior character traits’—everything that we work as individuals to overcome.”

“Boy,” said Hersh, “that hit home with Betty.”

For her class presentation, she disappeared and came back in tights with top hat and cane and “did a little soft shoe” singing “Me and My Shadow” a cappella. “It was so tender,” he said, “because she was singing with tears just streaming down her cheeks.”

The students, he said, were confounded. “But, I knew who she was and I knew what she had been through and seen her films and then to see her in this situation was an extraordinary experience.”

Hutton described for him the “wall between her show biz experience (where she found happiness on stage) and the real world.” It was obvious, he said, “she was looking for a father.”

“People loved her,” said Hersh. “They really appreciated what she was as herself.”

One friend, who has remained anonymous, said “Betty loved the coming and going; the yachts, conjuring up images of her Hollywood days; the Canada geese; the serenity of the water; and Newport Bridge in the distance, especially since it was designed by a woman.” And, she loved whipping up marvelous dishes from the Time-Life Good Cook series for dinner parties with close friends.

Fr. McGuire’s Tutelage

“Fr. Maguire,” Betty told Osbourne, “had the heart to understand me… he knew all the background of the alcohol.” And, for the first time in her life, she said, she didn’t have to pretend she wasn’t upset.

“Father said, ‘Betty, you’re just a hurt child. Let’s start from the word go.’” As she recovered, Fr. McGuire led her to God. “He loved me, Bob.” He had “Christ’s love—it totally surrounds you… like… the wonderful men… Jesus said in the Bible he was going to leave… (whom) I had never met…” The Catholic faith gave her great peace and serenity. “I don’t move anywhere without the rosary because… I’m scared inside… I’m never secure. And, that’s the way you have to be, Jolson said. You can’t give ‘em your heart if it’s not there, Betty.’”

Once she recovered, Hutton performed for Catholic gatherings and began to study under Fr. Maguire’s tutelage to master the grade and high school subjects she never learned as a child because she dropped out to sing. “(He) taught me from the 9th grade (her highest grade) to the 12th grade.”’

New Roles

“In Newport,” Hutton told Osbourne, “with Father I began to work with all troubled people… If I can take a soul that nobody wants any part of and pull them up by their bootstraps; that is a joy.” Amazingly, she would have worked with residents of the old Paramount Theatre at 77 Broadway across from City Hall—alive with her films decades earlier, now converted into low-income housing and a Salvation Army Thrift Shop.

In September 1980, she returned to Broadway for the musical Annie, playing Miss Hannigan for two weeks. Her grandchildren came to see her, which was “one of the great thrills” of her life, she told the Providence Journal-Bulletin.

Two years later, she performed at Capitol Records’ 40th Anniversary tribute, where she was the “emotional highlight,” the New York Times reported. The following March, she starred in PBS’s Juke Box Saturday Night clutching the rosary Father Maguire had given her.

“God’s plan,” she told the New York Times, would determine her showbiz future.

God had other plans.

Fr. McGuire, she told Osbourne, had “put all these books in my hands and when I felt I was ready I said, Father, I want to go to college. He said, ‘you’re ready now.’”

In September 1983, at age 62, Hutton enrolled as a student at Salve Regina University. Just like in her films, Hersh said, Hutton had “huge childlike energy” and “loved learning… and threw herself into it.”

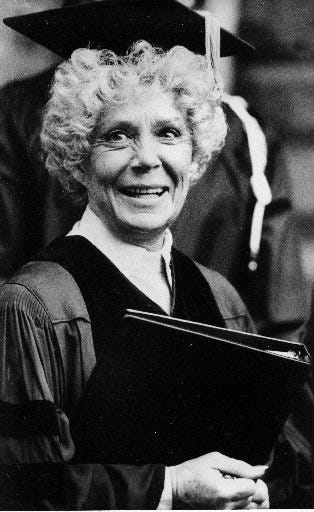

The following September, she was awarded an honorary doctorate, and graduated from Salve cum laude with a Master’s Degree in Liberal Studies in May 1986.

The day she graduated, May 18, 1986, she was “visibly nervous,” as she waited in the front row, the Providence Journal reported. But once “at center stage, a beaming Hutton opened her arms, blew one smooth, small kiss and bowed to her wildly applauding classmates… Grasping the diploma with both hands, she kept her left hand clenched around a strand of green ceramic rosary beads (the ones Fr. McGuire gave her.) Before descending to take her seat, she lifted the diploma heavenward and raised her eyes in a silent gesture of thanks.”

After graduating, Betty taught drama at Salve, which she said, “was a neat job because then I could begin to give Betty to them—not just the commodity, the hotdog.” She also taught at Boston’s Emerson College.

“Practically all the stars are in trouble,” she told priests she met in Rhode Island, as reported by AP. “You happen to see me talking honestly to you. It’s a nightmare out there! It hurts what we do in our private lives.”

On July 6, 1996, Father Maguire—the father she never had—died, after battling diabetes and heart disease for years. After his death, Hutton could not handle the pain of his absence. So, in March 1997, she moved to Palm Springs, where she lived until her death on March 11, 2007.

“The next time… there’s… thunder and lightning, that’s Betty raising hell with God,” about the movie she wants to make in heaven with Bing and the gang said Lyles at her memorial service.

A fitting image. For God, Lyles agreed, was always her best manager.

Mary Claire Kendall is author of Oasis: Conversion Stories of Hollywood Legends, published in Madrid under the title También Dios pasa por Hollywood, in which she writes about 12 legends of Hollywood, including Betty Hutton. She recently finished a biography about Hutton; as well Oasis II, featuring six more legends of Hollywood. Betty Hutton was the first Hollywood legend she wrote about, initially in Our Sunday Visitor in May 2007, then in Newport Life Magazine in a piece titled “Being Beautiful Betty,” published in May 2009, and in her Forbes column in March 2013 on which this article is based.

Yes, of course... thank you... article was based on one of my first articles about Betty, written for Forbes, now corrected... in the book, I dwell at length on how she "loved the man" -- Irving Berlin!

Very nice article. FYI the music to Annie Get Your Gun was written by Irving Berlin, not Gershwin.