Remembering Spencer Tracy, a theatrical legend and American treasure...

... on the 125th anniversary of his birth in Milwaukee, Wisconsin

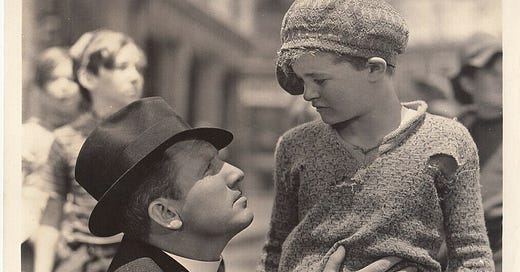

Today is the 125th anniversary of the birth of Spencer Tracy, known for Captains Courageous (1937), Boys Town (1938), San Francisco (1936), The Old Man and the Sea (1958), Judgement at Nuremberg (1961), among many other cinematic gems—the first two films winning him back-to-back Oscars.

I love writing about Spencer Tracy. He was hounded by his Catholic conscience and his father’s dream that he might become a priest, when all God wanted of him—his path to Heaven—was to be a great actor, which he achieved in spectacular fashion. Indeed, he was the greatest Hollywood had ever seen in the estimation of his peers. But he was weak and kept struggling, kept coming around to that path God had set out for him—all the while giving us some of America’s greatest films, great art, cinematic treasures which we cherish to this day.

And, on this day, when Spence was born 125 years ago, I give you this except from “Spencer Tracy Comes Full Circle” in Oasis of Faith: The Souls Behind the Billboard—Barrymore, Tracy, Cagney, Stewart, Guinness & Lemmon, which I hope you will have a chance to buy and read to your heart’s content. Meantime, God bless and Happy Birthday to Spencer Bonaventure Tracy, one of our greatest, on this his birthday!

***************************************************

You told the truth, didn’t you, Spence? You really could not sleep. And I used to wonder then, ‘Why?’ Why, Spence? I still wonder... What did you like to do? You loved sailing, especially in stormy weather... Walking? No, it didn’t suit you. That was one of those things where you could think at the same time—of this, of that.[i]

– Katharine Hepburn

Ethel Barrymore’s advice at the start of Spencer Tracy’s theatrical career was profound. She must have had an intuitive feel for him. “Relax, just relax,” was just the salve his soul needed.[ii]

As a teen, he felt called to be a priest—that, or possibly, a doctor. But he did not have the grades for Latin—or chemistry, for that matter. More importantly, he had the passion to act. [iii] “I wouldn’t have gone to school at all if there’d been any other way to read the subtitles in films,” he said.[iv]

His peers considered this twice Oscar-winning star Hollywood’s greatest actor. He also sometimes acted like Hollywood’s greatest sinner. The essence of this complex man was the guilt he felt—not understanding or accepting, given his tense, exacting nature, that God gave him the soul of an actor, not that of a priest. Then, too, there was the “loneliness,” which his friend Garson Kanin believed was the “single wellspring” of his tortured psyche and his “genius.”[v] In God’s plan, his angst infused his work with unmatched brilliance, while, off camera, he grappled with that distorted image of God as a stern judge. “Life,” he told Bert Reynolds, was something he was not good at.[vi] But, an honest tally—not the severe accounting his brooding Irish nature concocted—shows a man with a generosity of spirit that only comes from God. Who is Love. That spirit catapulted him to the top of his profession.

His father’s son

Spencer Tracy was born on April 5, 1900 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin in the family’s rented duplex apartment at 30th Street and St. Paul Avenue in Merrill Park, a lower middle-class rural yet urban neighborhood in the west end, just south of “Grand Avenue.” This vibrant and modern community, teaming with tots, eschewed saloons and livery stables. It was graced by St. Rose of Lima Church headed by a dynamic pastor, Father Patrick H. Durnin, who was skilled at wooing his prosperous parishioners, including 19 millionaires—encouraging them to frequent the sacraments and enrich the church coffers.

Spencer’s father, John Edward Tracy, was an accountant for Sherburn S. Merrill’s Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railroad. He hailed from Freeport, Illinois, known for its Henney Buggies and Stover windmills and bicycles. Spencer’s grandfather, John D. Tracy, an Irish immigrant, had settled in Freeport in 1870 to run the Rock Island Track and helped found the city bank. He had fled Galway during the Great Famine of 1854, initially settling in Mazomanie, Wisconsin, then Savannah, Illinois where he rose to roadmaster and raised his first family with his wife Letitia. She bore him three children, including two daughters who became nuns. After Letitia’s death, John D. married Mary Guhin from County Kerry, who bore him four sons, including Spencer’s father John, born in 1873.

It is a mystery how John, Jr., a lace curtain Irish Catholic in largely Methodist and Presbyterian Freeport, met and began courting Episcopalian Caroline “Carrie” Brown. She was the daughter of Edward S. Brown, a prosperous flour miller, who owned a grain and feed store, and was descended from famed Providence, Rhode Island mercantilist, Nicholas Brown, whose son founded Brown University. John attended St. Mary’s Catholic and Notre Dame, while Carrie attended Freeport High, followed by a brief stint in college. It is surmised they met at the family store or at the bank where John was a teller. He was “a charming Irishman” with a ready wit and wealth of “funny stories.”[vii] But it was no laughing matter that the two were keeping company. And, when the scandal broke that she was seeing an Irish Catholic from the Liberty Division bordering the railroads, John Sr. imposed a curfew on his two elder sons, no doubt at Mr. Brown’s insistence.

But Carrie and John were in love and quietly married on the evening of August 29, 1894 at the Brown’s elegant home on upper Stephenson. They moved to LaSalle, Wisconsin where John worked as a bank teller. After work, he drank. Though not a mean drunk, he proved unreliable at the bank, prompting the couple to return to Freeport, where his father got him a bookkeeper’s job with the St. Paul Railroad and welcomed the couple into their home, where brothers Andrew and Will and Will’s wife, also lived. When their first child, Carroll Edward Tracy, was born on June 15, 1896, the quarters became so cramped that they moved to the Browns’ more spacious home. But John’s excessive imbibing irked his in-laws. So, when a position opened up in Milwaukee, he mustered all of his charm to land the job, soon moving his family out—to everyone’s relief.

Upon arriving in Milwaukee, Carrie discovered that she was pregnant again and, nine months later, she delivered, to her great disappointment, another boy. By the time John’s unmarried sister Jenny arrived on April 22 to take the infant to St. Rose’s to be baptized, Carrie, still reeling from the birth, had yet to pick a name. Her heart had been so set on having a girl that she had only picked the name, “Daisy,” after her friend Daisy Spencer. Jenny suggested using Daisy’s last name instead. For the saint’s name they settled on Bonaventure—the same name Letitia’s daughter Catherine had taken upon entering the convent.

In 1901, John, hard at work supporting his growing family, was promoted to general foreman on the St. Paul Railroad. But his new offices had him passing by saloons after work and he began getting sauced en route home to abstemious Merrill Park. As usual, his life began unraveling, but, by the grace of God, he found a new job as a clerk, away from the saloons, in the new galvanized roofing shingle business at Milwaukee Corrugating Company. A year later, in 1902, the family resettled in Bay View, South Milwaukee, where the Kinnickinnic River flows into Lake Michigan. Like Merrill Park, Bay View was established by its corporate overlord—in this case, Milwaukee Iron Company—for employees at the steel mill, built in 1867. Initially iron and steel workers flocked there from Great Britain. Then, as nearby factories sprung up, Irish mill hands plus a colony of Italians and throngs of Poles and Germans, came seeking work.

As the family settled into the new neighborhood, Carroll began school and Spence unleashed his hyperactive reign of terror. An early neighbor, Mrs. Henry Disch, remembers fondly how, initially, “He was in dresses… bubbling with life. I don’t believe he ever sat still… (to read) a book… His brother Carroll was a quiet boy... but Spence was always outside with the boys.” One night when Mrs. Disch hosted the family for dinner, Spence restlessly kicked the legs of nearby chairs as the adults chatted away. Bored to tears, he began entertaining himself by peeling the “raised enamel dots” off cherished salt and pepper shakers she had just purchased for $1.50, until the dots were just a “neat little mound beside his plate.” [viii]

His restlessness may have derived, in part, from his family’s constant moves and his father’s frequent change of jobs, at least every two years, mostly in the shipping and freighting business. Then, too, there’s evidence the family moved because of Spence’s poor school attendance record. By the time Spence was 11, while his family had lived in at least seven different rented homes, he had changed schools even more often.

Some of this energy was channeled spiritually—at Sunday mass he attended regularly with his father at the Church of the Immaculate Conception, while his mother, whom he was closest to, identifying with here sympathetic side, remained at home. The three-year-old soaked in the Divine Liturgy and the various ways in which the congregation participated, albeit, he would not have received Holy Communion until he was ten, the year Pope Pius X granted children this privilege. He loved his father no less, admiring his virility[ix] and these weekly pilgrimages to church nurtured and solidified the father-son bond. “Dad was a tough, decisive, no-nonsense man, and there was never any doubt that we’d be raised as Catholics,” said Carroll Tracy. “When we were old enough, Spence and I both became altar boys. Later in the Catholic schools, Spence got very interested in the theology of the Church. One of dad’s greatest hopes was that one of us would become a priest.”[x]

Yet, Spence was anything but angelic. When he was just seven, he went missing for an entire day until he was found with two friends “Mousie” and “Rattie” in an alley back of a saloon in the distant South Side of the city. [xi] This disappearing act became a regular routine, accompanied with great drama as he returned, often before officially leaving. Then, one Sunday, while they were all at church, nine-year-old Spencer, who had remained behind in the care of a nurse, set the house on fire. When they got home, the fire department was fighting to douse the flames. “No one apparently knew how the fire started, least of all the young picture of perfect innocence, Spencer,” wrote Kay Proctor some 30 years later. “It was attributed to defective wiring.”[xii] The truth is, the little live wire had started it.

As he got older, Spence began hanging with tough kids beyond Bay View, frequently bringing home his rough pack of friends—feeding them and sending home one or two of them with his own clothes in place of their tattered togs. “I can honestly say that back of every one of Spencer’s exploits was something fine like sympathy, generosity, affection, pride, or ambition,” Carrie said. “There was not a mean bone or thought in him.”[xiii]

As for naysayers, Carrie, whose faith in him was unbounded, would always say, “You wait and see.” At the same time, she also kept him in line.

Carroll, too, watched over his restless brother to the point of obsession, as if trying to compensate for their father’s frequent boozing—absences that Spencer worried related to something he had said or done, when, in fact, it was due to alcoholism that plagued his paternal grandmother’s side, impacting his father’s behavior and, even more severely, that of his brother Will. Spencer would play hooky by ducking into the nearby local storefront theatre, Comique, not far from Trowbridge School, where he was enrolled. The ‘moving pictures’ mesmerized him. Carrie managed to curtail his truancy, if just a bit, by refusing to let him go to the theatre if he skipped school. It was no contest. Missing feats of derring-do with Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford, William S. Hart and Tom Mix was worse than sitting through spelling.

The more enduring solution lay in the choice of school. Freeport it was—where initially he spent summers with his grandparents. Now, the other nine months, he was also attending Freeport’s Union Street School and working in the family feed store. It was a structured environment that proved beneficial to Spence—so much so that when he turned nine, his parents decided to enroll him in St. John’s Cathedral School in downtown Milwaukee, three miles from Bay View. There the watchful Dominican nuns administered wallops of discipline—whacking his hand with a ruler for transgressions. But they also inspired him. He was fascinated by his Catholic faith, spending three hours twenty minutes each week studying it—the same amount of time he spent in reading class. And, he began going to confession, learning about sin, repentance and forgiveness, and receiving Holy Communion after the 12-hour fast. Unfortunately, he also began mimicking his father’s disappearing act. But, one day, when he planned to make his great escape, the little bit of food he managed to stuff into an old suitcase got him only so far before he realized he had exhausted his supply, prompting an about-face.

His love of the theatre and of the Faith merged when he discovered the art of performance while serving as an altar boy at Mass—the ritual, garb, and words, dramatically spoken in Latin, all essential elements of the theatre, as well. Afterwards, his mother said, he would run home and light and extinguish candles for hours. Then, too, he began re-enacting for friends and neighbors the oft-watched silent films he had committed to memory. He was also a great magician. But some stunts didn’t end up so magically—like that time he set the house ablaze because, in fact, he was playing with matches and cigarettes.

But he managed to survive and thrive and, in 1915, he graduated from St. Rose’s—his 15th (possibly 16th) school—and earned his intermediate diploma. Then, it was on to Kansas City, where his father was working a short-term job. There, he attended St. Mary’s High School. But it was a brief sojourn. Upon their return to Milwaukee, 16-year-old Spence entered Marquette Academy (a Jesuit prep school for Marquette University), where his already-kindled interest in theology burned brightly, earning him his highest grades. Not long after entering Marquette, Carroll told Kanin, “Spence all of a sudden decided to go for priest!” Everyone was pleased if a little surprised, he said. “Spence had been—up to that time—a full scale hell-raiser.” [xiv]

“You know how it is in a place like that,” Spence told Kanin. “The influence is very strong, intoxicating. The priests are such superior men—heroes. You want to be like them—we all did. Every guy in the school probably thought some—more or less—about trying for the cloth. You lie in the dark and see yourself as Monsignor Tracy, Cardinal Tracy, Bishop Tracy, Archbishop—I’m getting gooseflesh!”[xv] …

For the rest of the story, see Oasis of Faith: The Souls Behind the Billboard—Barrymore, Tracy, Cagney, Stewart, Guinness & Lemmon.

Photo Credits: Wikipedia Commons. Top photo: An MGM press photo of Spencer Tracy and Martin Spellman in Boys Town (1938); Next photo: An MGM Spencer Tracy Boys Town still.

[i] Bill Davidson, Spencer Tracy: Tragic Idol, (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1987), p. 216.

[ii] Ethel Barrymore, Memories: An Autobiography (London: Hulton, 1956), p. 218.

[iii] In those days, it was not uncommon for a young man to enter the “seminary,” at the least, to eliminate the possibility he had a priest’s vocation, considered the highest calling. My own grandfather, Frank Biberstein, also born in 1900, attended Charles Borromeo seminary in Philadelphia for a time.

[iv] David A.Y.O. Chang, “Spencer Tracy’s Boyhood: Truth, Fiction and Hollywood Dreams,” Wisconsin Magazine of History, Autumn 2000, p. 32.

[v] Garson Kanin, Tracy and Hepburn: An Intimate Memoir (New York, NY: The Viking Press, Inc., 1971), p. 14.

[vi] Bert Reynolds reminiscing about Spencer Tracy for Turner Classic Movies.

[vii] Peggy Hoyt Black, “The Tough Tracy Kid,” Street & Smith’s Picture Play, February 1937.

[viii] Hoyt Black, “That Tough Tracy Kid,” p. 92.

[ix] Anne Edwards, A Remarkable Woman: A Biography of Katharine Hepburn, (New York: William Morrow and Company, 1985), p. 190.

[x] Davidson, p. 12.

[xi] Kay Proctor, “Ex-Bad Boy,” Screen Guide, April 1937.

[xii] Proctor, “Ex-Bad Boy.”

[xiii] Proctor, “Ex-Bad Boy.”

[xiv] Kanin, p. 24.

[xv] Kanin, pp. 24-25.

Mary Claire Kendall is author of Oasis: Conversion Stories of Hollywood Legends. The sequel, Oasis of Faith: The Souls Behind the Billboard—Barrymore, Cagney, Tracy, Stewart, Guinness & Lemmon, was published summer 2024. Her biography of Ernest Hemingway, titled Hemingway’s Faith, was published Christmas 2024 by Rowman & Littlefield, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing. She writes a regular bi-monthly column for Aleteia on legends of Hollywood and hidden screen gems.